My Sale Extended and Woodland birds in Donegal

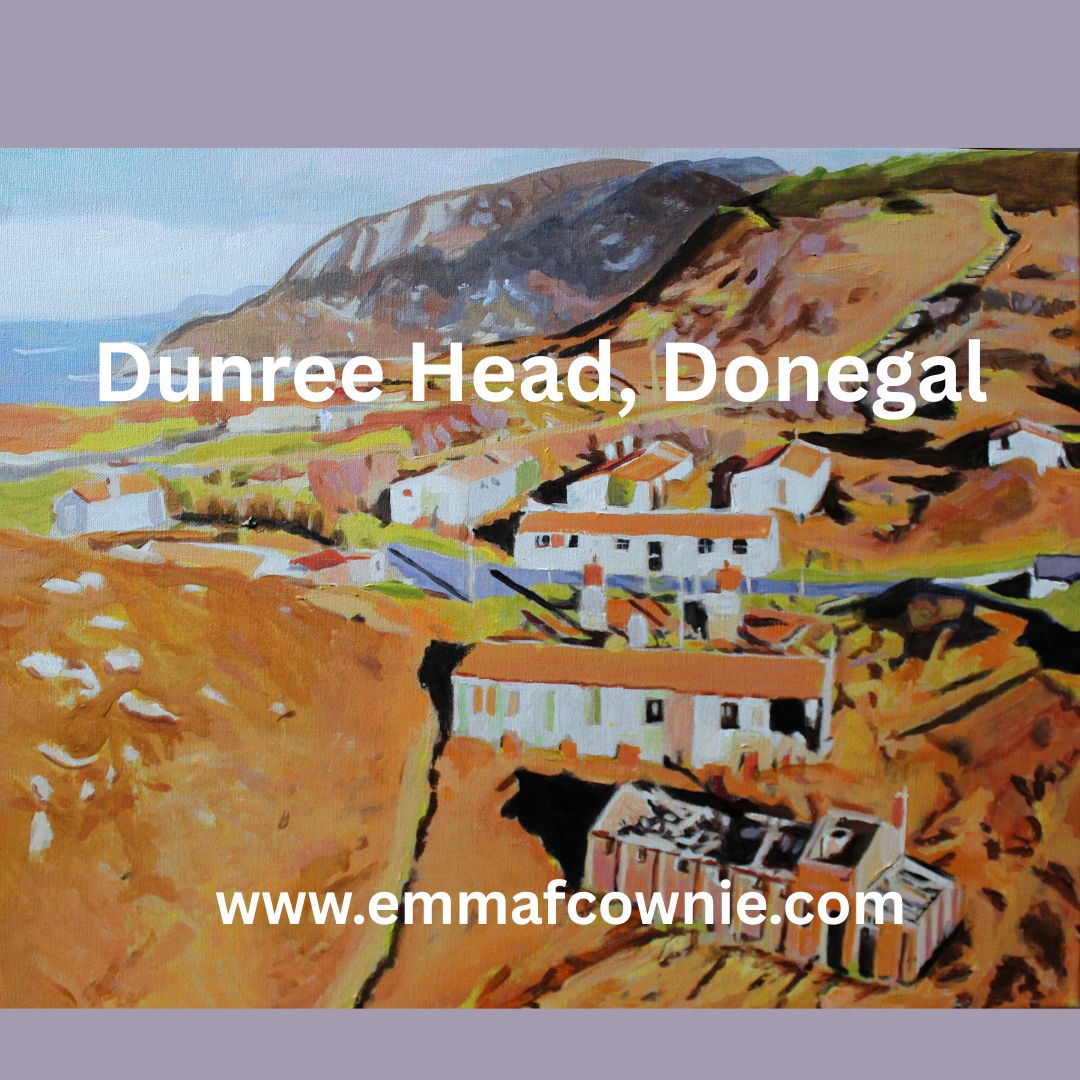

Today is the shortest day of the year. Its very dark up north here. The morning are very dark yet I find it hard to sleep. When the sun appears it illuminates and reveals a verdent but slummering landscape. I am always looking for flashes of red to paint in the deepest winter. In the past it might be a coat, or a door. Today it is a red roof on an old stone cottage. The old houses are disappearing fast here.

This part of Inishowen near Dunaff feels remote. Maybe that’s because we drove through up and through the Urris Hills and Mamore gap to get here. It’s all small long roads like this one. Its tucked away in a north western corner of Inishowen, Malin Head is to the north, close by. I look forward to the days slowing getting longer.

One of the joys of acrylic gouache is that it dries very quickly and is opaque – so it lends itself to this sort of mark making.

I have tried several times this year to write more about developments in AI (and Art) but I keep giving up because I keep getting sucked down “rabbit holes” and I find it hard to see the wood for the trees. OK here goes – I dislike and distrust AI. It’s overhyped. The visual stuff looks horrible. It’s dangerous. Unregulated it is going to cause a lot of damage in our societies/brains/education/communities/environment. I think that is the nub of it. We are told that our glorious AI-powered future is imminent, yet what we’ve actually got is unprofitable, unsustainable generative AI that has an unassailable problem of spitting out incorrect information. Its an expensive dead end.

If you would like to read a more articulate assessment of the current state of (digital) economy I can recommend Ed Zitron article on the Rot Economy – its in a slightly different league to the Cory Doctorow’s Enshitification explanation of why platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest and Youtube used to be good to use but are now annoying and almost impossible to use. Can you find the video you just watched on Youtube? Me neither. I have struggled with WordPress ever since it “updated” itself to include all sorts of AI features I will never use. My Windows 11 PC isnt much better. It forever flips a “news” screen in front on my eyes in the midst of me doing something else, like typing a blog

Ed says “Things are being made linearly worse in the pursuit of growth in every aspect of our digital lives, and it’s because everything must grow, at all costs, at all times, unrelentingly … Our digital lives are actively abusive and hostile, riddled with subtle and overt cons. Our apps are ever-changing, adapting not to our needs or conditions, but to the demands of investors and internal stakeholders that have reduced who we are and what we do to an ever-growing selection of manipulatable metrics.” I was delighted (and not surprised) that 95% per cent of the more than 10,000 people in the UK who had their say over how music, novels, films and other works should be protected from copyright infringements by tech companies called for copyright to be strengthened and a requirement for licensing in all cases or no change to copyright law. AI companies have no right to our work.

I have decided to give up on writing about AI and so instead I will you with the best commentry on this current state of madness I have come across: AI Peas by Stephen Collins.

Dun Fhraoigh in Irish means, “Fort of the Heather” – it has been a fort at Dunree for thousands of years, since the Bronze age (over 4000 years ago). When you see the chunk of rock that the “modern” day fort (well Napoleonic era) for has been built on, you understand why.

Its a big chunk of rock! (photo credit: Emma Cownie)

Its location, on the cliffs of Dunree Head, is great for observing and controlling ships moving up and down the majestic Lough Swilly, one of Ireland’s three glacial fjords.

The English built this sturdy fort on the chunk of rock c. 1812-3 with a draw-bridge! The enemy back then, as readers of Jane Austen will know, was the French forces of Napolean Bonaparte. (The story of Jane Austen’s Donegal nieces is worthy of a BBC/RTE mini-series in its own right; linking Kent, Ramelton and Gweedore). The French had attempted landing in Lough Swilly in 1798 with a force of about 8,000 men, which was repelled at sea. The Royal Navy anchored ships in the Lough. There were a lot of big guns here, nine 24-pounders were in 1817. There was once a Martello-type in the centre of the old fort but it was demolished c. 1900, as it obstructed the field of fire from the new fort on the summit of Dunree Hill.

Although the Irish Free State was created in 1922 and they followed (and still follow) a policy of political neutrality, the British army did not leave Dunree until 1938. This was because Lough Swilly was a “Treaty Port”, and it remained under British military control for defensive purposes. During the Second World War, it was under control of the Irish Army and it played an integral role in safeguarding Ireland when a number of anti aircraft guns were added to site. The waters off the coast of Donegal are under threat today from Russia’s so-called “shadow fleet”.

I am not particularly interested in military hardware, although I know plenty of people in the world are. I have not been in the military museum. What did take my interest, however, were the barracks. There were brick buildings but also a lot of decaying iron huts that the gunners had lived in. I am nosy and I enjoy seeing how people lived. Although, frustratingly, most of that has gone. There tiny glimpses; brick chimney stacks, the odd rusting bedstead but not a lot.

A little further up (a steep) hill from Fort Dunree and the barrack buildings is Dunree Lighthouse. This a puzzling lighthouse. I am used to lighthouses being built atop of great pillars like the one across the Swilly water at Fanad.

The one at Dunree, however, has no tower. It doesnt need one. The light is at ground level. The “ground” however its up high on the cliff way above the Fort. A lantern attached to a house for the Lighthouse Keeper was built, and the light established on 15th January 1876. The light was a non flashing one with a two wick oil burner. Sadly, for the lighthouse keeper, technology did away with his job in 1927 when this light was replaced in December 1927 with an “unwatched acetylene with a carbide generating plant attached to the station”. The light was later converted to electricity in 1969. It must have been a great place to live.

The lighthouse keeper’s house has a spectacular view across the Lough. Its built of local rubble stone masonry, this building retains its early form and character. Its visual appeal and expression is enhanced by the retention of much of its original fabric including timber sliding sash windows. Both the house and the lantern were built by McClelland & Co. of Derry. The simple outbuilding and boundary walls are very elegant too.

The views at Dunree are spectacular. Lough Swilly is quite majestic, even on an overcast day. Perhaps, it’s particularly dramatic on a overcast day with the shifting light and colours. You can walk up Dunree Hill and look over towards the Urris Hills and Dunree Bay (Crummies Bay).

There is a regular bus service from Buncrana, a coffee house, museum and public toilet. It might be a good idea to go before they start work on revamping the place!

See more paintings of Inishowen Peninsula here

Read More

https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/buildings-search/building/40901824/dunree-fort-dunree-donegal

https://www.govisitdonegal.com/blog/january-2024/between-waves-and-war

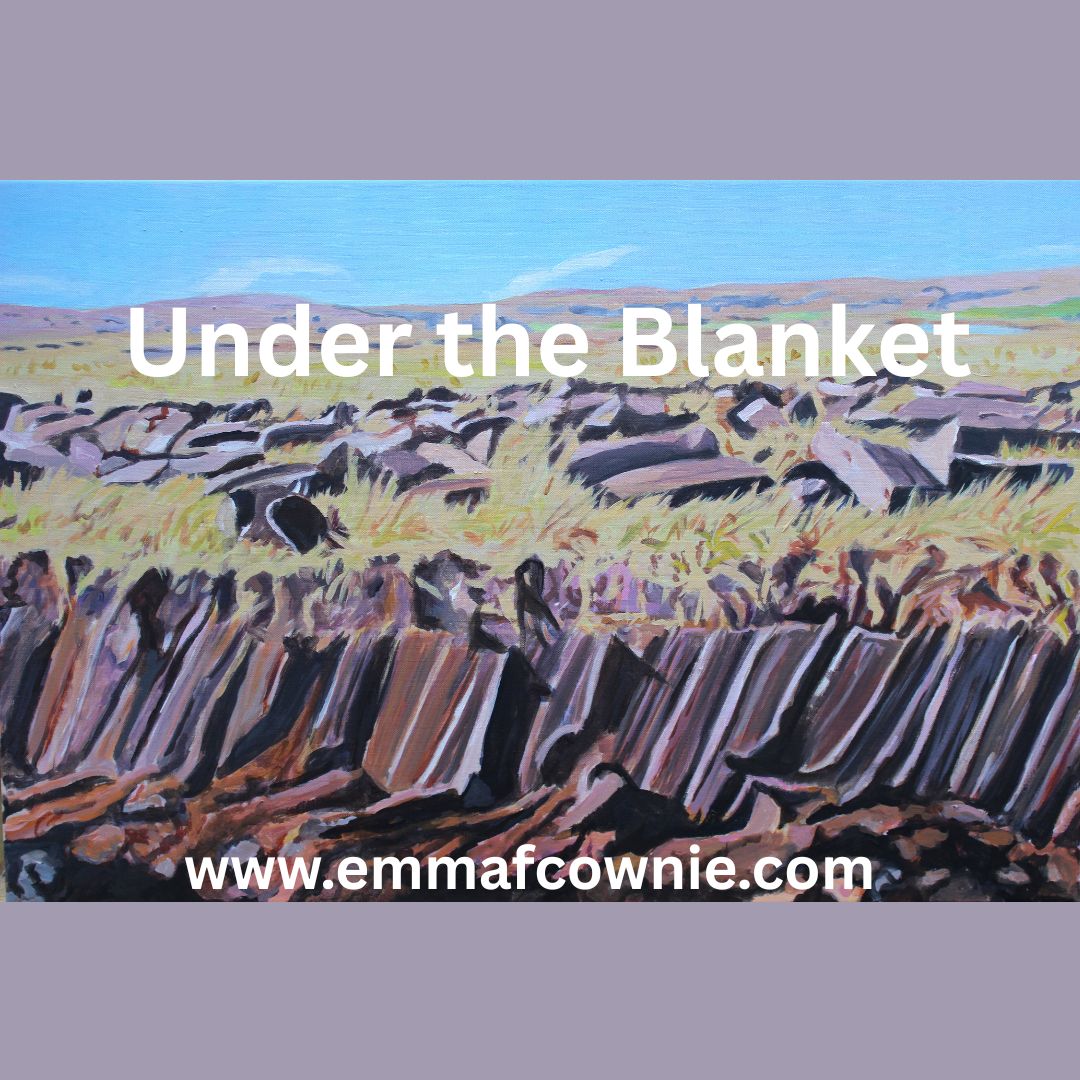

Ireland was once covered in a massive sheet of ice. Then about ten thousand years ago it retreated and trees and grasses sprang up to cover the rocky landscape. Today those trees are long gone. Farmers came and cleared them about 6,000 years ago and the continual rains from the Atlantic soaked and washed the soil reducing the mineral content making it more acidic. Plants like sphagham moss helped keep the land wet. So now West Donegal is covered in something called blanket bog. Blanket bog is a type of peatland found in only a few parts of the world with cool, wet and, usually, oceanic climates. It covers 3% of the world but contains a third of all the carbon in the world.

I love the blanket bog – it covers vast areas. It is a seemingly empty landscape. On an overcast day it has an exhilerating bleakness. On a sunny day, it hints at what a prehistoric Ireland might have looked like (plus a few wolves and lots of red deer). There are few, if any, paths through the bogland. If you venture on the land in summer it is springy underfoot. Most of it is drained with ditches along the road and narrow bog roads leading to “nowhere”.

For generations people who lived on the boglands drained the land then cut and dried the peat, also called turf, to burn. This was cheap fuel to cook and heat their homes. In a land with no oil or coal, the turf was essential. The landscape across west Donegal is marked with the long scars of peat banks. Cutting it is back-breaking work. In the past the surface of the bog was mostly cut away by hand using the traditional turf spade or sleán. Further South mechanised extraction is apparently the norm, using chain cutter, digger, sausage, hopper and milling machines. In Donegal, however, it is still cut by hand.

The Irish government used to burn turf on an industrial scale, enough to fuel a couple of power stations, up until very recently, 2020 in fact. People with “turbary rights” can cut and burn sod peat on their land for their own domestic uses but they are not meant to sell it. However with fuel poverty, older people in particular, will buy it to use it in winter. A load of turf may cost as little as 200 Euros (about 230 US dollars) and can last months.

The government is trying to discourage this not only because of the enviromental costs but also because of the pollution it causes. It smells delicious but its smoky and very bad for the lungs, especially if you have asthma.

There are moves to encourage the rewetting of the bogs. Targets have been set by the EUand a few pilot schemes in Donegal and a lot more in the Midlands, have been rolled out, Cloncrow Bog Natural Heritage Area is a great example of a rewetted raised bog. However, much more funding is needed from the government to encourage widespread adoption and to help the 4% of the population for whom turf is their main source of heating.

The boglands are abundant with wildlife and have been an important part of Irish culture. Bogs were seen as liminal zones – watery places often are. They were seen as places of both life and death—fertile ground for spirits, fairies, and supernatural beings. The bog was also believed to be the gateway to the Otherworld, where fairies, spirits, and even the dead could cross between realms. Many bog bodies and ancient artifacts were likely put there as ritual offerings to appease gods or supernatural forces.

If you want to look at some bog bodies this site has some good photos. I wont post them here, I never really got over looking at the poor soul in the British Museum (Lindow Man) who died in a Cheshire bog. I was fascinated by his face but couldn’t help thinking he could never imagine his mortal remains being looked at by all and sundry over 2000 years later.

One of the most famous mythical figures associated with the bog is Fionn Mac Cumhaill (Finn McCool), the legendary warrior of the Fianna. Some stories say that he and his warriors roamed the boglands, using them as a hiding place during battles.

Bogs have also inspired wonderful poetry. This is my favourite-

Green, blue, yellow and red –

God is down in the swamps and marshes

Sensational as April and almost incred-

ible the flowering of our catharsis.

A humble scene in a backward place

Where no one important ever looked

The raving flowers looked up in the face

Of the One and the Endless, the Mind that has baulked

The profoundest of mortals. A primrose, a violet,

A violent wild iris – but mostly anonymous performers

Yet an important occasion as the Muse at her toilet

Prepared to inform the local farmers

That beautiful, beautiful, beautiful God

Was breathing His love by a cut-away bog.

+ Patrick Kavanagh (One of Ireland’s most famous poets, from Monaghan, d.1967)

And finally…Seamus Heaney’s Poem “Digging” In 1995 Seamus was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature.

Read about Seamus Heaney’s Bog Poems

NOTE: I did not use AI to research and/or write this and I did not use it to “improve” it. I would rather my writing was human and imperfect.

Read More about Boglands

https://www.nature.scot/landscapes-and-habitats/habitat-types/mountains-heaths-and-bogs/blanket-bog

https://talesofforgottenirishhistory.substack.com/p/the-bog-of-allen?utm_medium=web

Termon House is set above a pebble beach at the north end of Maghery Strand on the West Coast of the Rosses area of Donegal. The elegant white house was most likely built by the Marquis Conyngham or by his predecessor, Montgomery in the 1770’s for the land agent, whose duty it was to collect rent from the local tenants on behalf of the absentee landlord. A Jamaican-born man named Ralph Spence Philips, was in occupancy at Termon House in the 1820s.

In 1822 the previous years extremely wet weather rotted all the potatoes in the area which resulted in famine. This was happening across Ireland and around a million individuals came to depend upon government aid during this particular crisis. Government agents in Dublin Castle allocated funds for acquisition of foodstuffs in Ireland, to be distributed to the poor at reduced prices or without cost, and to finance local relief works, such as roads, canals and harbours, or other projects deemed of benefit.

It may well have been Philips who initiated the building of the Famine Walls around the property as a means of feeding the local starving population, although he had no tenants of his own. The Public Works Committee in Dublin Castle, however, rejected Philips application for reimbursement and this meant a personal loss to him of £1500 from paying the labourers at a rate of 1d per day!

There is another theory, however, that is that it was the Reverend Valentine Pole Griffith, the Protestant Rector at the height of the Great Famine, 1845-1850, who had the walls built. The Rev Griffith was one of the leading members of the Famine Relief Committee, who worked heroically on behalf of the poor. He set up public works in Maghery, would attend meetings all over the Rosses and write to anyone who he thought could help. The land around Termon House was owned by the Church of Ireland it may well be he who arranged for the massive walls to be built along the road there. On the day we visited it was overcast and my photos do not to justice the scale and extent of the walls.

You can see the famine walls on the right hand side of the house and to the far left side of the outhouses in my painting of Termon House (below). The rocks in the foreground are natural part of the rocky Rosses landscape.

What is undisputed is that this extraordinary and extensive system of walls standing approximately three metres high (10 foot)! The extensive system of tall walls built during this famine around his land is a testament to these hungry builders as they have withstood over 190 years of Atlantic storms.

Today, beautiful Termon House is leased by the Irish Landmark Trust and is available for holiday rental.

More Information

See my paintings of West Donegal here

“Announcing SAOIRSE by @charleen_hurtubise, a powerful novel set between the United States and Ireland about a woman who runs from her traumatic past and the secrets she carries to survive. Coming February 24, 2026.”

With artwork by me!

See more original paintings of Donegal here