My Sale Extended and Woodland birds in Donegal

Today is the shortest day of the year. Its very dark up north here. The morning are very dark yet I find it hard to sleep. When the sun appears it illuminates and reveals a verdent but slummering landscape. I am always looking for flashes of red to paint in the deepest winter. In the past it might be a coat, or a door. Today it is a red roof on an old stone cottage. The old houses are disappearing fast here.

This part of Inishowen near Dunaff feels remote. Maybe that’s because we drove through up and through the Urris Hills and Mamore gap to get here. It’s all small long roads like this one. Its tucked away in a north western corner of Inishowen, Malin Head is to the north, close by. I look forward to the days slowing getting longer.

One of the joys of acrylic gouache is that it dries very quickly and is opaque – so it lends itself to this sort of mark making.

Termon House is set above a pebble beach at the north end of Maghery Strand on the West Coast of the Rosses area of Donegal. The elegant white house was most likely built by the Marquis Conyngham or by his predecessor, Montgomery in the 1770’s for the land agent, whose duty it was to collect rent from the local tenants on behalf of the absentee landlord. A Jamaican-born man named Ralph Spence Philips, was in occupancy at Termon House in the 1820s.

In 1822 the previous years extremely wet weather rotted all the potatoes in the area which resulted in famine. This was happening across Ireland and around a million individuals came to depend upon government aid during this particular crisis. Government agents in Dublin Castle allocated funds for acquisition of foodstuffs in Ireland, to be distributed to the poor at reduced prices or without cost, and to finance local relief works, such as roads, canals and harbours, or other projects deemed of benefit.

It may well have been Philips who initiated the building of the Famine Walls around the property as a means of feeding the local starving population, although he had no tenants of his own. The Public Works Committee in Dublin Castle, however, rejected Philips application for reimbursement and this meant a personal loss to him of £1500 from paying the labourers at a rate of 1d per day!

There is another theory, however, that is that it was the Reverend Valentine Pole Griffith, the Protestant Rector at the height of the Great Famine, 1845-1850, who had the walls built. The Rev Griffith was one of the leading members of the Famine Relief Committee, who worked heroically on behalf of the poor. He set up public works in Maghery, would attend meetings all over the Rosses and write to anyone who he thought could help. The land around Termon House was owned by the Church of Ireland it may well be he who arranged for the massive walls to be built along the road there. On the day we visited it was overcast and my photos do not to justice the scale and extent of the walls.

You can see the famine walls on the right hand side of the house and to the far left side of the outhouses in my painting of Termon House (below). The rocks in the foreground are natural part of the rocky Rosses landscape.

What is undisputed is that this extraordinary and extensive system of walls standing approximately three metres high (10 foot)! The extensive system of tall walls built during this famine around his land is a testament to these hungry builders as they have withstood over 190 years of Atlantic storms.

Today, beautiful Termon House is leased by the Irish Landmark Trust and is available for holiday rental.

More Information

See my paintings of West Donegal here

Summer in Donegal is full of light. Even if its damp summer there is still lots of light. The northly latitude sees to that. It only seems to get properly dark for a couple of hours after midnight and dawn comes impossibly soon. So its great for painting and getting out and about but the light is not so interesting for photography or sketching, especially if, like me, you like lots of strong shadows. So my paintings are usually based on images that are captured in the autumn months. Otherwise, mornings and evening are best for interesting colours and shadows.

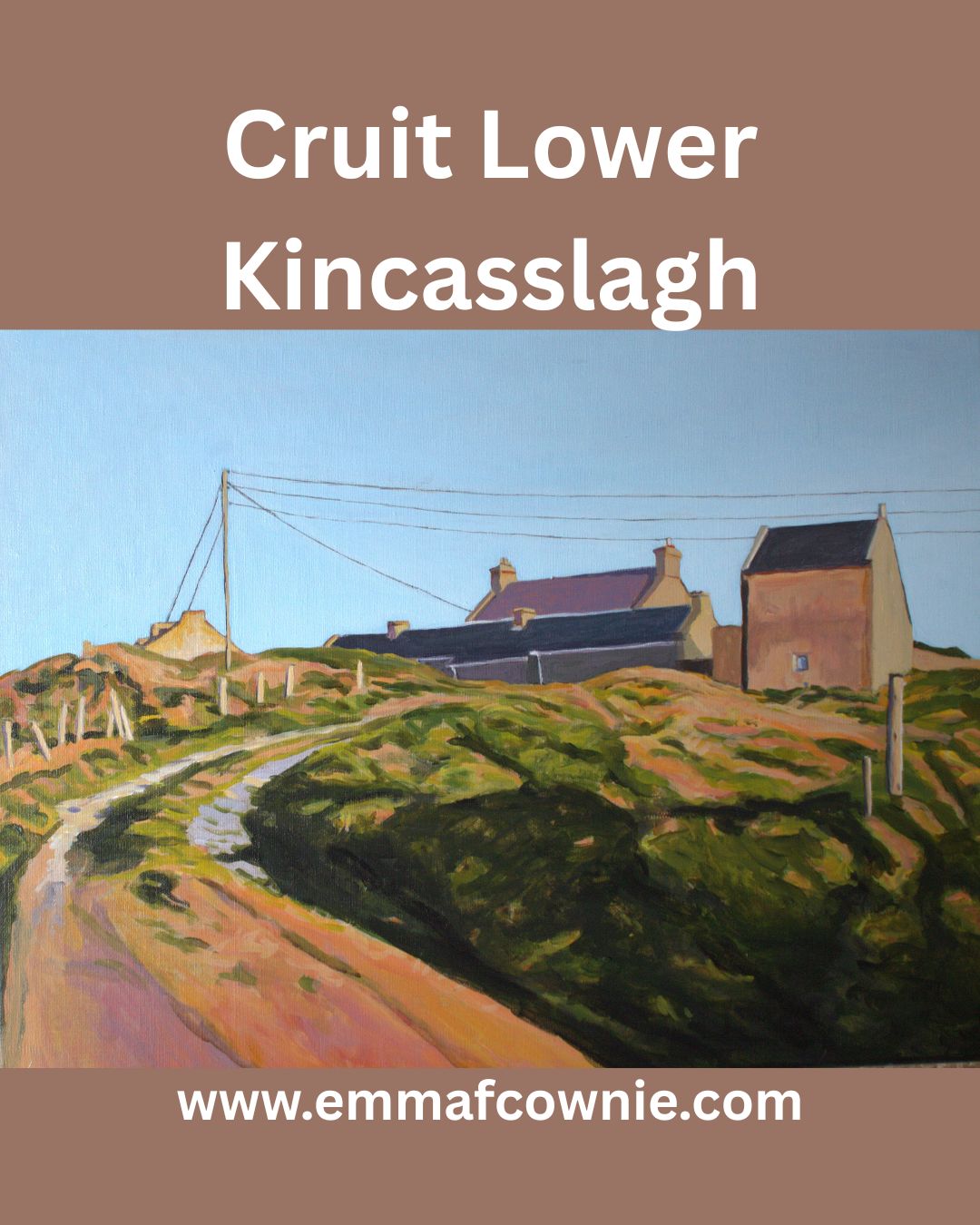

Cruit Island is one of my favourite places in Donegal. It’s rocky and sparsely populated but is accessible by a handy bridge.

We have driven past the collection of farm buildings at Cruit Lower many times but I only managed to capture an image I liked enough to paint this spring. It was an uncharacteristically warm and sunny run of days this May.

The farm has long fascinated me as you have to drive through it. These through roads through farms are not unusal in rural areas in Ireland (and Wales). Informal tracks through a collection of farm buildings, now divided by tarmac.

Lower Cruit was for sale last year and I had a good look at it online. It was interesting as you can only glimpse some of the buildings from the road. I cant remember how much the asking price was. Getting on for a million Euro, maybe. Way out the reach of a poor artist! You got a lot for that; a collection of beautiful historic buildings (some pre-famine era) and access to a beautiful beach and some really incredible views of the West of Donegal. Here are some of the photos from the website. I dont know who bought it but I really hope they look after the beautiful old buildings.

More information about Cruit Lower

https://www.buildingsofireland.ie/buildings-search/building/40904015/cruit-lower-co-donegal

1901 census information http://donegalgenealogy.com/1901cruitlowr.htm

https://www.donegalcottageholidays.com/cruitisland-cruitisland

https://www.booking.com/city/ie/kincaslough.en-gb.html

We have been living with a lot of uncertainty since summer last year. This is why I have found it difficult to write regularly. Last summer, Biddy, our aged Collie-cross was so frail I didn’t come to Donegal with her. I didn’t think the long bumpy car journeys would be fair on her. The vets are an hour away. She was pts in November last year. It was an honour to look after her in her final days and I still miss her. I will write about Effie in a separate post, soon.

It is with a heavy heart that I say that we are planning to leave Donegal. It’s a difficult place to live without family near by. It’s a stunning place and the recent sunshine has really highlighted that. It is possibly the most beautiful landscape I have ever seen and I will be very sad to leave. I am not entirely sure where we are going. I will let you know when we know.

In the meantime, I have painted a series of small paintings of Arranmore Island.

If you are interested in buying an Arranmore painting you can here: https://emmafcownie.com/product-category/paintings-ireland-emma-cownie/donegal-paintings-emma-cownie/donegal-islands

To Celebrate the New Year I am giving 30% off all work on my website – to get the discount you have to enter a code at the checkout. Where’s the code? Join my email list and it will be sent to you, automatically. The sale ends on 15th January.

If you have already joined my mailing list and haven’t had my latest newsletter with the sale code check your SPAM folder.

Have you seen this Apple advert? Take a moment to watch it. It makes my blood run cold. Surprisingly the tech bros at Apple thought it was a good idea to show this advert which depicts a tower of creative tools and analog items (like paint, trumpets and record players), being crushed into the form of the iPad. It’s a pretty grim vision of the future. It a good visual metaphor for what is happening to creatives right now.

This year has been the toughest year I have experienced as an artist, for a myriad of reasons, and the art market seems to be struggling generally. Yes there’s war in Ukraine and the Middle East (and elsewhere in the world) and “the Cost of Living Crisis” and terrible cold and wet weather in the British Isles hasn’t helped either.

It seems evident that it’s more difficult getting my work seen. I cant help but think that AI and the “enshitification of the internet” is at least partly responsible. I feel a bit like I am being slowly crushed by the Apple crusher. It’s sapping my creative juices. I don’t quite know what to do about it. Cory Doctorow explains how enshittification works “It’s a three-stage process: first, platforms are good to their users. Then they abuse their users to make things better for their business customers. Finally, they abuse those business customers to claw back all the value for themselves. Then, there is a fourth stage: they die.”

This is probably the reason why I can’t find any useful results on google – lots of top ranking website are full of AI nonsense. It’s also why fewer people are seeing my work on the internet. My posts are pretty much hidden on Facebook, Instagram and invisible on X. Images of my paintings do not show up on Google as much as they did say 3 or even 6 months ago. Many other artists report a similar decline in interest from potential customers.

I have started to visit my local library again in search of real books with in- depth facts. The only decent thing on Google these days is Wikipedia. I find that Youtube playlists are so random as to be useless and a search on Pinterest results in either pins I have seen before (in other words I have already saved them) or one unrelated to the search term I just used. Tech companies are burning up the planet with their massive data centres in the hope that one of them will “win” the AI battle and then charge us all for what used to be better quality and free.

What’s this got to do with you? Everything. Doctorow says that enshittification is coming for all industries. “From Mercedes effectively renting you your accelerator pedal by the month to Internet of Things dishwashers that lock you into proprietary dish soap, enshittification is metastasising into every corner of our lives. Software doesn’t eat the world, it just enshittifies it.” Think about your printer – a new printer is cheap as chips but the ink costs a fortune and you cant use non-proprietary ink and your printer will know, and refuse to work.

Corry Doctorow’s big hope is that “Stein’s Law will take hold: anything that can’t go on forever will eventually stop…if everyone is threatened by enshittification, then everyone has a stake in disenshittification.” Actually, there’s a lot more to it than that. You’ll have to read his articles to find out what USA and EU are planning to do to break the monopolies of the big tech comapnies.

I just hope that independent artists like me survive the process or else everyone will have to console themselves with souless AI-derived art their ipad/smartphone/tablet device instead.

See below for some scary examples of AI “Art”. It’s a nonsense view of Derry if you didn’t know.

Just in case some of you are saying. It’s Londonderry not Derry. AI is no better at conjuring up a view of Londonderry. Take a look! Although there is a river this time.

How about Three Cliffs Bay? I have painted that many times. Sure AI will do better at ripping me off. Well, no.

Yes, we can laugh at AI’s efforts and say they look nothing like those places or my paintings but it’s all doing damage. AI can never replace human creativity. AI cannot suffer and struggle like humans. It just produces a wierd pastiche of the thing it is meant to be. It’s expensive rubbish. It’s costing us dearly. Emissions from data centers of the likes of Google, Microsoft, Meta and Apple may be 7.62 times higher than they let on.

We can reverse the enshittification of the internet. Don’t accept those tracking cookies. Try a different search engine. Stay on the website rather than downloading apps (you can use ad blockers on the website you can’t on the app). Don’t buy everything via Amazon if you can buy it in a real life shop.

We can halt the creeping enshittification of every digital device. Put down your phone/tablet and read a book or look at a painting made by a real human being. Join artists’ mailing lists so you can still follow their work no matter what the big platforms do to hide their work.

Oh, did I mention I have a 20% off sale on? Starting Sunday until Monday 14th. You have to join my mailing list for the code 20% code but you can unsubscribe at any time.

Read more

Cory Doctorow on Enshittification of the Internet – https://pluralistic.net/2023/08/27/an-audacious-plan-to-halt-the-internets-enshittification-and-throw-it-into-reverse/

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2024/sep/15/data-center-gas-emissions-tech

I am delighted that Peter Zantingh, a Dutch blogger, wrote this an account of Gola and my work. I have translated it for you to read (well, Google did). You can read the original here.

“In the autumn of 2018, Emma Cownie looked out from the Irish mainland at an island she could not get to. It seemed so close. She could see the rocks off the coast and beyond them, scattered seemingly at random across the rolling land, the whitewashed cottages. Some were abandoned, others clearly still inhabited, or used as summer homes.

Gola Island is one of 365 islands off the Irish coast. It is just two square kilometres in size. No one knows exactly how many people live there, because there are more in the summer than in the winter. Ferryman Sabba only goes up and down between June and September.

But in 2022, there were fifteen people living on Gola, according to official figures.

Emma Cownie is a British artist. She studied medieval history at Cardiff University and taught at a secondary school for a while. On 29 February 2012, she was hit by a car. It was, in retrospect, what prompted her to take up painting full-time. The days in front of the class were exhausting, almost all contact with other people in fact, she was startled by every sudden sound. A few years before the accident her dog had been run over on a busy road.

Painting helped.

In the days after she had stood on the mainland looking at those houses in the distance she painted Spring Light on Gola. It came, she told me, ‘out of a kind of longing for the island’.

In the spring she went again. It was early April, sunny but chilly, a cold wind blowing along the coast. Her husband Séamas was with her, their dog Mitzy too. To get the best view of the island – again there was no ferry – they walked along long stretches of beach and climbed on granite boulders, almost pink in the spring light. From here she could see the houses that had recently been renovated and modernised.

That summer she was finally able to go there. ‘There are hardly any cars’, she told me about it. ‘Just a few tractors, no telephone poles or electricity pylons and only a few other people. Other than that, just birdsong and wind. It’s bliss.’

*I emailed Emma Cownie last month with a simple question. One of her paintings was used on the cover of one of my favorite books, Foster by Claire Keegan. I wanted to discuss that book in my newsletter, and I would like to show that painting as well. Would that be okay? I would mention her name and link to her website.

She responded the same day, and we got to talking. She said that the painting I had asked about was called Traditional Two Storey House, Gola, and that it was nice to hear from someone from the Netherlands, because although she regularly sees Dutch campers in Donegal, the county in the northwest of Ireland where she lives part of the time, she has never sold work to anyone from the Netherlands.

The title of the painting made me curious. Gola? What was that? That’s how I became fascinated with the island in my own way.

At one time, there were about two hundred people living there, who made a living from fishing and small farms. But after 1930, the population began to decline. Especially in the winter, it was easier to earn money in the cities, especially those of Scotland and England, and fewer and fewer people returned for the summers. In 1966, the island’s school closed; with only nine pupils (there used to be sixty), it no longer had a right to exist. The few families with young children were forced to move to the mainland – and once the last family with children had left, the community was doomed.

I read this last in Gola: The Life and Last Days of an Island Community (1969) by F.H. Aalen and H. Brody, which I ordered for a few euros on boekwinkeltjes.nl or Abebooks. I think I mainly wanted to know what happened when the last ones left. How does a group of people dissolve itself?

Brody, a sociologist who wrote the part about the last days of the community by the two authors, saw a kind of laconic group feeling among those who were still there at the end of the sixties. Everyone wanted to stay, if the rest stayed too. Everyone thought it was okay to go, as long as everyone else went too.

The most intriguing aspect of each islander’s account of his own predicament is his insistence that it all depends on the others. […] The general attitude is one of wait and see – what the others do. But all of the Gola people are waiting on one another in this way, and do not seem to mind the impasse that this conditional planning involves. Of ten islanders who related their plans, nine said they would like to stay, but it depended on the others. One man said he would stay so long as he had a dog with him, and could not see any advantage to life away from the island. Apart from that one man, all stated they would be glad to remain on Gola, but did not really mind leaving.

The authors also contributed to a short documentary for the Irish public broadcaster RTÉ from the same year, which shows how one family, the O’Donnells, leaves the island. They lock the door and walk with their dog, a long-haired collie, to a motor boat in the harbor. They are all wearing black. (Screenshots from the film below)

Five people remained: fisherman Eddie, fisherman Tadhg, postman Nora and her husband John, and ninety-year-old Mary. It would not be long for them either.

What was left behind? The island had no shop, no pub, not even a church. “The islanders worship on the mainland when the weather is good enough to make a safe crossing,” Brody wrote in 1969. Just over thirty houses remained, most in poor condition. The schoolhouse and the post office. Wooden boxes and fishing nets in the harbour, where a statue of the Virgin Mary, housed in a stone shrine, continued to look out. Two pegs on a washing line.

Between 1969 and 2002, Gola was an uninhabited island. In Dances With Waves: around Ireland by Kajak (1998), Brian Wilson (not the Beach Boys guy, another Brian Wilson) writes about the time he went ashore during his nearly two-thousand-mile kayak trip all the way around Ireland. He hoped to find some peace and shelter that day, but he encountered “the eerie atmosphere of a ghost town”. Fishing boats lay rotting in the harbour among the washed-up debris.

But he found something more hopeful in the cottages. They were “abandoned, but not in decay”.

[…] one felt as though, like faithful dogs, they were just waiting for their owners to return. More than that, it was as if the island itself was still waiting. And the people came again. They came back. Somewhere around the turn of the millennium, the first ones crossed. Today, most of the cottages are still uninhabited, but in summer the sounds and movements of people join those of the cormorants, guillemots and gannets.

Emma Cownie has made more than 25 paintings of Gola in recent years.

For Traditional Two-storey House, Gola, the painting that made me contact her, she returned to the ‘rules’ she had set for herself a few years earlier. These rules – not coincidentally – coincide with how she wanted to organise her life after the car accident and the difficult time that followed: no cars, no people, bright light.

Furthermore, there must be shadows, preferably diagonal, in simple shapes. The painting must be about the interplay between shadows and man-made constructions, the tension between 3D buildings and 2D shadows.

She also wanted to think longer and better about colour. Not to choose the brightest colour, purely for effect, as she had done before, but to work more subtly. In a new series of works based on the houses on Gola Island, including Traditional Two-storey House, she resisted the urge to make the shadows very dark, the sky pale pink and the grass yellow and bright green. “I tried to keep the shapes and colours as simple as possible without it being a cartoon,” she told me. “I wanted to capture the essence of the place.”

She painted the picture in January 2021, during a Covid-19 lockdown in Wales, where she was then living. That summer, she and Séamas moved to Donegal, in the north of Ireland.

It was the following summer, 2022, that she was approached by the prestigious London publishers Faber & Faber: they wanted to use Traditional Two-storey House for the cover of Claire Keegan’s Foster, originally published in 2010.

“I didn’t realise what an honour it was until I got a copy of the book and read it,” she said. “I cried at the end.”

Is there a writing lesson in this? I don’t know. Maybe that there’s more to everything. Maybe it’s worth following your interests and fascinations without reservation. To notice it – this interests me, this grabs me – and follow that line, see where it takes you.

We have been exploring Malin Head a fair bit recently. I really enjoy it’s wildness and dramatic beauty. It’s one of those rare places that is quiet. By quiet, I mean a lack of human busyness. There’s plenty of nature noise like the wind, the hissing of the grasses and leaves as they are blown.This has to be one of the most exposed spots in Ireland.

There is good scattering of robust cottages and relatively few cars. The narrow, winding roads mean that they are not pelting by. Its the quiet and still I hunger for – even when its blowing a gale! The fresh air here is like a refreshing drink of water.

Here are two new Malin Head paintings. The first is “Midsummer at Malin Head” which is a sturdy cottage surrounded by vigorous growths of monbretia. We are a bit early for its distinctive firey orange flowers – the come out from July to September.

The second painting is John’s Cottage, Malin Head (photography with permission of John Gallagher). John was born in the cottage but he now lives with his family (and dog) in a neighbouring cottage a stone’s throw from here.

In the distance are the Urris Hills, also on the Inishowen Peninsula. We spent two days last autumn there, looking for my husband Séamas’s drone crashed on Croaghcarragh (a peak between Urris Hills and Mamore with Mamore Gap in between) after he flew it backward into the mountainside! I spent a longtime waiting for him as various spots on the mountain, looking out towards Dunduff, Clonmany and Malin. The view was magnificent in that direction too. The howling gale that threatened to blow us off the mountain was pretty sobering. Fortunately, the drone was found and it still worked after a night out in the wilds. DJI make pretty tough little drones!

Summer Post-Script

For those who cannot not make it to West Donegal, here’s a brief video of my viewing gallery all set up by Séamas.

If you are thinking of visiting here’s a google map of our location

More Information on Inishowen