The robots are coming for our Art. Artists are losing their ability to make a living and we will all be poorer financially and creatively for it. I have been trying to ignore Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Art. Don’t get me wrong. In its place, AI can be very useful. I am aware that as I mistype this text, my computer is offering up corrections. That’s an example of AI. The human element, however, is vital to decide whether to accept the suggested changes or not.

So What’s the Problem?

The type of AI I am concerned with here is something called Generative AI. It is based on deep-learning models that can generate high-quality text, images, and other content based on data (which can be text, numbers and or images) they were “trained” on. The supposed promise of generative AI is that it will generate the image in your imagination if you can describe it. Although, it may take a few goes to find a version that you like.

The thing is that I don’t like it. It doesn’t matter if they are AI “paintings”, illustrations, cartoons or photographs. I find them a bit unnatural and creepy. Many people describe these images as soulless.

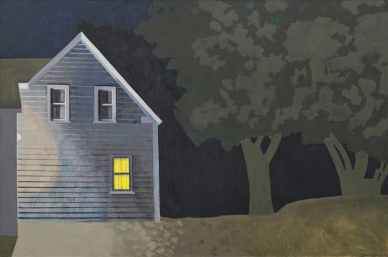

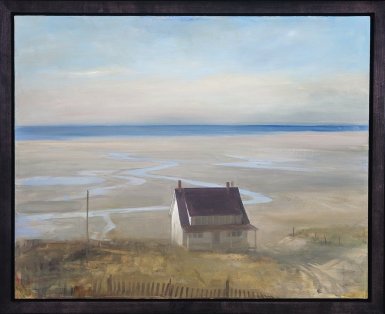

One of the joys of being an artist is creating something from nothing. Well, not nothing exactly but being inspired by an idea, a view or a scene and drawing, painting or photographing to make something that did not exist before. The process is an act of creation, from noticing a particular colour or light, composing the layout of the work to the execution of the piece. The landscapes I paint mean something to me; they capture a place, a feeling or a time. I hope they mean a lot to the people who buy them too.

The problem I have with AI generated Art is that it is automated Art. It has no meaning. Work generated by AI isn’t novel. It’s banal—or worst of all, in the art world—derivative.

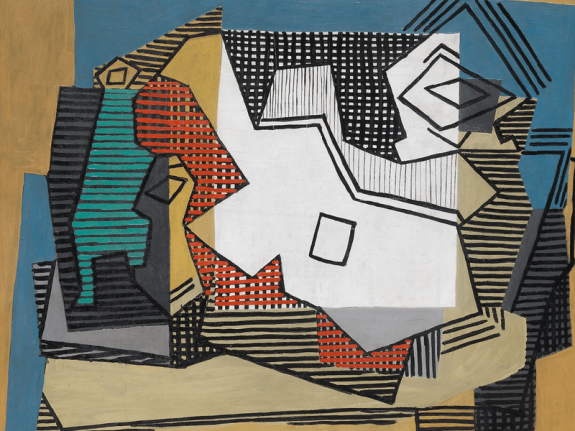

I know, someone will say: “Good Artists Copy: Great Artists Steal”. I am not sure who said this first. A lot of people are credited with saying it including Pablo Picasso, Steve Jobs, T.S. Eliot and Igor Stravinsky.The difference is that those artists were inspired by what had gone before and gave it their own interpretation. Picasso’s later work only makes sense in the context of the African sculptures that inspired him. Picasso, however, was a very skilled draughtsman and supremely confident painter and you can see from the images below that he was not merely copying the sculptures but had imbibed, digested and reformulated their essence in his own way.

Compare Picaso’s work with an AI version:

These AI generated images (above ), however, are pale imitations and are quite “dead” in comparison to Picasso’s work. They come from a site called artvy.ai which specialises in generating art in the style of named artists. They include a disclaimer that their images are meant to “provide inspiration” and not be “replicas of the artists’ work”. This is significant as the AI Art companies say this to avoid being sued for copyright infringement. These images also miss the physicality of real world art – the actual texture of the paint and the surfaces. An AI version of Jackson Pollock or Claude Monet just doesn’t cut it for me; without the texture of the paint they have had their spirit removed.

Some commentators see this use of others’ work as inspiration for new work by humans as broadly analogous to what AI art does. Yes, there are artists who use AI art in their own creations as a means or tool to create meaning. American artist Eric Millikin is one such artist, he uses AI in an interesting and genuine creative manner as one of many tools. That’s different. Whether he owns the copyright to this work, however, is a grey area. People who create work using AI do not own the copyright. Most jurisdictions, including Spain and Germany, state that only works created by a human can be protected by copyright.

The problem is that AI Art is getting better and they are using living artists’ work to improve. In doing this, they are killing off thousands of jobs, such as illustrators, cartoonists and designers. AI companies are not going to compensate those people. It will also put young people off from going to art school. Artists will have to give up Art as they can’t make a living at it. Why bother spending years honing your skills and unique style if AI can do it better and faster? Why bother taking 10-20 years learning colour theory and anatomy if AI is just going to rip off your work in seconds?

Jon Stewart – a bit sweary but very funny take on AI

This is because AI needs real artwork images to “train” on/with. This is known as scraping. Generative AI has only been around for 2 years and already it has gobbled up most of the internet. Last year a list of 16,000 artists whose work had allegedly been scrapped by AI company Midjourney was leaked by John Lam Art.

You can read this list here . It includes artists such as Jackson Pollock, Pablo Picasso, Bridget Riley, Damien Hirst, Rachel Whiteread, Tracey Emin, David Hockney and Anish Kapoor.

Interestingly, Hollywood writers also realised that AI was a profound threat to their livelihoods. Last year they organised a strike that lasted 146 days. They demanded that the studios not use AI to generate “original” scripts. In September, they won. News and Tech companies have also ramped up action against AI scrapping. Last summer, Twitter (now X.com) banned AI from scrapping tweets on its site. Nearly 90 percent of top news outlets like “The New York Times”, “The Guardian” and the BBC also block AI data collection bots from OpenAI and others. Big companies like Getty Images are also suing image-generating AI for scraping their data without permission.

Individual visual artists are not doing so well. In Japan the battle is already lost. AI companies can use “whatever they want” for AI training “regardless of whether it is for non-profit or commercial purposes, whether it is an act other than reproduction, or whether it is content obtained from illegal sites or otherwise.” This position led to Japan being called a “machine learning paradise.”

In the USA the artists are fighting back. That list of 16,000 artists that John Lam leaked came to 24 pages when printed out. It forms Exhibit J in a class action brought by 10 American artists in California against Midjourney, Stability AI, Runway AI and DeviantArt for copyright infringement.

Unfortunately, the Federal US judge hearing the case, in late October 2023, sided with the AI companies against the 10 artists. The judge made a distinction between works that are copyrighted and works that are not. This is despite the fact that the U.S. Copyright Office considers a copyright to exist “from the moment the work is created,”. However, the agency notes that copyrights have to be registered works to bring a lawsuit for alleged infringement in the USA.

The fight is not over yet. However, the judge invited the plaintiffs to refile an amended claim, which they did in late November 2023, with some of the original plaintiffs dropping out and new ones taking their place and adding to the class, including other visual artists and photographers. The artists argue that the AI companies, by scraping the artworks and using them to train AI to produce new, highly similar works, is infringing their copyright.

The companies’ new counterargument claim they do not replicate the artists’ original work exactly. The arguments are quite lengthy and you can read about them in more detail here.

It doesn’t have to be this way, some companies such as Adobe, Shutterstock and iStock are using AI Art ethicially without infringing artist’s copyright. As AI generated Art cannot be copyrighted that means that big corporations like MacDonalds, Nike, Disney won’t ever want to use it for logos and merchandising as they will not be able to sue anyone for copyright infringement. So it many end up as regarded as little more than very fancy clip Art. They will have destroyed thousands of creative jobs for what?

So how do we fight the Rising Tide of AI?

There are a number practical but steps you can take:- Don’t post your work online. That’s a tough one if you are hoping customers will find your work online. Karla Ortiz, one of the 10 artists in the California lawsuit against AI companies, did that at one point.

If you do publish images of your work you can watermark your works – yes, if you apply heavy watermarking, posting such a picture defies the purpose of the publication itself. Light watermarking will not prevent your work from being used by an AI.

Make sure that your pictures are posted on-line in a lower quality. Again that’s a tough one if you are hoping to sell online. Also you can publish copyright notices on your website

Use incorrect tagging, so robots will not consider your artwork as proper for image generation. For example instead of #modernartpainting you use #happycowsonameadow

Some AI companies provide ways to opt images out of being used in training data. You can visit https://haveibeentrained.com/ and block your website from being crawled by AI bots (go to https://haveibeentrained.com/domains and add your domain) You can also check if your image was trained on by some biggest image-generating AIs.Of course, your work is protected only if people who manage AIs training engines opt-in to respect your opt-out.

Finally you can do what is called “poisoning the well”. Researchers at the University of Chicago have created cloaking tools for artists to add to images they upload to the internet that is intended to poison the AI database. These are called Glaze and Nightshade, they are free to download and can interfere with AI models directly. It is recommended that artists use Glaze first and then Nightshade on their work. These tools mess up training data in ways that could cause serious damage to image-generating AI models but are not obviously visible to human eyes, they are time-consuming though. I downloaded the program but my PC didnt have enough memory/RAM to run it. I am waiting to get an account so I can do it online on their web version.

This poster for Connemara

This poster for Connemara