I am delighted that Peter Zantingh, a Dutch blogger, wrote this an account of Gola and my work. I have translated it for you to read (well, Google did). You can read the original here.

“In the autumn of 2018, Emma Cownie looked out from the Irish mainland at an island she could not get to. It seemed so close. She could see the rocks off the coast and beyond them, scattered seemingly at random across the rolling land, the whitewashed cottages. Some were abandoned, others clearly still inhabited, or used as summer homes.

Gola Island is one of 365 islands off the Irish coast. It is just two square kilometres in size. No one knows exactly how many people live there, because there are more in the summer than in the winter. Ferryman Sabba only goes up and down between June and September.

But in 2022, there were fifteen people living on Gola, according to official figures.

Emma Cownie is a British artist. She studied medieval history at Cardiff University and taught at a secondary school for a while. On 29 February 2012, she was hit by a car. It was, in retrospect, what prompted her to take up painting full-time. The days in front of the class were exhausting, almost all contact with other people in fact, she was startled by every sudden sound. A few years before the accident her dog had been run over on a busy road.

Painting helped.

In the days after she had stood on the mainland looking at those houses in the distance she painted Spring Light on Gola. It came, she told me, ‘out of a kind of longing for the island’.

In the spring she went again. It was early April, sunny but chilly, a cold wind blowing along the coast. Her husband Séamas was with her, their dog Mitzy too. To get the best view of the island – again there was no ferry – they walked along long stretches of beach and climbed on granite boulders, almost pink in the spring light. From here she could see the houses that had recently been renovated and modernised.

That summer she was finally able to go there. ‘There are hardly any cars’, she told me about it. ‘Just a few tractors, no telephone poles or electricity pylons and only a few other people. Other than that, just birdsong and wind. It’s bliss.’

*I emailed Emma Cownie last month with a simple question. One of her paintings was used on the cover of one of my favorite books, Foster by Claire Keegan. I wanted to discuss that book in my newsletter, and I would like to show that painting as well. Would that be okay? I would mention her name and link to her website.

She responded the same day, and we got to talking. She said that the painting I had asked about was called Traditional Two Storey House, Gola, and that it was nice to hear from someone from the Netherlands, because although she regularly sees Dutch campers in Donegal, the county in the northwest of Ireland where she lives part of the time, she has never sold work to anyone from the Netherlands.

The title of the painting made me curious. Gola? What was that? That’s how I became fascinated with the island in my own way.

At one time, there were about two hundred people living there, who made a living from fishing and small farms. But after 1930, the population began to decline. Especially in the winter, it was easier to earn money in the cities, especially those of Scotland and England, and fewer and fewer people returned for the summers. In 1966, the island’s school closed; with only nine pupils (there used to be sixty), it no longer had a right to exist. The few families with young children were forced to move to the mainland – and once the last family with children had left, the community was doomed.

I read this last in Gola: The Life and Last Days of an Island Community (1969) by F.H. Aalen and H. Brody, which I ordered for a few euros on boekwinkeltjes.nl or Abebooks. I think I mainly wanted to know what happened when the last ones left. How does a group of people dissolve itself?

Brody, a sociologist who wrote the part about the last days of the community by the two authors, saw a kind of laconic group feeling among those who were still there at the end of the sixties. Everyone wanted to stay, if the rest stayed too. Everyone thought it was okay to go, as long as everyone else went too.

The most intriguing aspect of each islander’s account of his own predicament is his insistence that it all depends on the others. […] The general attitude is one of wait and see – what the others do. But all of the Gola people are waiting on one another in this way, and do not seem to mind the impasse that this conditional planning involves. Of ten islanders who related their plans, nine said they would like to stay, but it depended on the others. One man said he would stay so long as he had a dog with him, and could not see any advantage to life away from the island. Apart from that one man, all stated they would be glad to remain on Gola, but did not really mind leaving.

The authors also contributed to a short documentary for the Irish public broadcaster RTÉ from the same year, which shows how one family, the O’Donnells, leaves the island. They lock the door and walk with their dog, a long-haired collie, to a motor boat in the harbor. They are all wearing black. (Screenshots from the film below)

Five people remained: fisherman Eddie, fisherman Tadhg, postman Nora and her husband John, and ninety-year-old Mary. It would not be long for them either.

What was left behind? The island had no shop, no pub, not even a church. “The islanders worship on the mainland when the weather is good enough to make a safe crossing,” Brody wrote in 1969. Just over thirty houses remained, most in poor condition. The schoolhouse and the post office. Wooden boxes and fishing nets in the harbour, where a statue of the Virgin Mary, housed in a stone shrine, continued to look out. Two pegs on a washing line.

Between 1969 and 2002, Gola was an uninhabited island. In Dances With Waves: around Ireland by Kajak (1998), Brian Wilson (not the Beach Boys guy, another Brian Wilson) writes about the time he went ashore during his nearly two-thousand-mile kayak trip all the way around Ireland. He hoped to find some peace and shelter that day, but he encountered “the eerie atmosphere of a ghost town”. Fishing boats lay rotting in the harbour among the washed-up debris.

But he found something more hopeful in the cottages. They were “abandoned, but not in decay”.

[…] one felt as though, like faithful dogs, they were just waiting for their owners to return. More than that, it was as if the island itself was still waiting. And the people came again. They came back. Somewhere around the turn of the millennium, the first ones crossed. Today, most of the cottages are still uninhabited, but in summer the sounds and movements of people join those of the cormorants, guillemots and gannets.

Emma Cownie has made more than 25 paintings of Gola in recent years.

For Traditional Two-storey House, Gola, the painting that made me contact her, she returned to the ‘rules’ she had set for herself a few years earlier. These rules – not coincidentally – coincide with how she wanted to organise her life after the car accident and the difficult time that followed: no cars, no people, bright light.

Furthermore, there must be shadows, preferably diagonal, in simple shapes. The painting must be about the interplay between shadows and man-made constructions, the tension between 3D buildings and 2D shadows.

She also wanted to think longer and better about colour. Not to choose the brightest colour, purely for effect, as she had done before, but to work more subtly. In a new series of works based on the houses on Gola Island, including Traditional Two-storey House, she resisted the urge to make the shadows very dark, the sky pale pink and the grass yellow and bright green. “I tried to keep the shapes and colours as simple as possible without it being a cartoon,” she told me. “I wanted to capture the essence of the place.”

She painted the picture in January 2021, during a Covid-19 lockdown in Wales, where she was then living. That summer, she and Séamas moved to Donegal, in the north of Ireland.

It was the following summer, 2022, that she was approached by the prestigious London publishers Faber & Faber: they wanted to use Traditional Two-storey House for the cover of Claire Keegan’s Foster, originally published in 2010.

“I didn’t realise what an honour it was until I got a copy of the book and read it,” she said. “I cried at the end.”

Is there a writing lesson in this? I don’t know. Maybe that there’s more to everything. Maybe it’s worth following your interests and fascinations without reservation. To notice it – this interests me, this grabs me – and follow that line, see where it takes you.

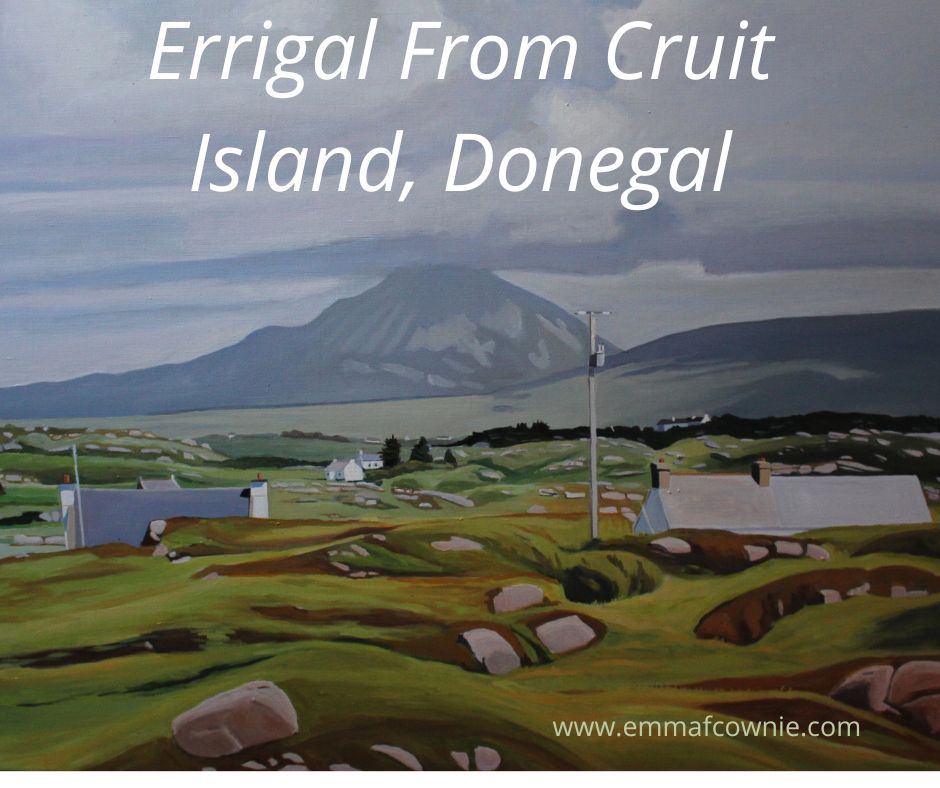

This poster for Connemara

This poster for Connemara